Human Nature and Suffering

Routledge Mental Health Classic Edition

Human Nature and Suffering

‘Human Nature and Suffering is a landmark work that sets the stage for decades of research and practice of a psychotherapy better suited to the realities of evolved human motivation and emotion. The re-release of this classic is a godsend for this generation of psychologists and the next.’

Dennis Tirch, PhD, Founder, The Center for Compassion Focused Therapy

Human Nature and Suffering is a profound comment on the human condition, from the perspective of evolutionary psychology. Paul Gilbert explores the implications of humans as evolved social animals, suggesting that evolution has given rise to a varied set of social competencies, which form the basis of our personal knowledge and understanding.

Gilbert shows how our primitive competencies become modifi ed by experience – both satisfactorily and unsatisfactorily. He highlights how cultural factors may modify and activate many of these primitive competencies, leading to pathology proneness and behaviours that are collectively survival threatening. These varied themes are brought together to indicate how the social construction of self arises from the organisation of knowledge encoded within the competencies.

This Classic Edition features a new introduction from the author, bringing Gilbert’s early work to a new audience. The book will be of interest to clinicians, researchers and historians in the fi eld of psychology.

Paul Gilbert, OBE , is Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Derby and has been actively involved in research and treating people with shame-based and mood disorders for over 30 years. He is a past President of the British Association for Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapy and a fellow of the British Psychological Society. He was awarded the OBE for contributions to mental health in 2011.

Routledge Mental Health Classic Edition

The Routledge Mental Health Classic Edition series celebrates Routledge’s commitment to excellence within the fi eld of mental health. These books are recognized as timeless classics covering a range of important issues, and continue to be recommended as key reading for professionals and students in the area. With a new introduction that explores what has changed since the books were fi rst published, and why these books are as relevant now as ever, the series presents key ideas to a new generation.

The Plural Psyche (Classic Edition)

Personality, morality and the father Andrew Samuels

Evolutionary Psychiatry (Classic Edition)

A new beginning, second edition Anthony Stevens and John Price

The Wounded Healer (Classic Edition)

Countertransference from a Jungian perspective David Sedgwick

Four Approaches to Counselling and Psychotherapy (Classic Edition)

Windy Dryden and Jill Mytton

The Therapeutic Use of Self (Classic Edition)

Counselling practice, research and supervision Val Wosket

Depression (Classic Edition)

The evolution of powerlessness Paul Gilbert

Human Nature and Suffering (Classic Edition)

Paul Gilbert

Human Nature and Suffering

Classic Edition

Paul Gilbert

Classic Edition published 2017 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2017 Paul Gilbert

The right of Paul Gilbert to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

First edition published in 1989 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

First edition reprinted in 1992 by Routledge

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Gilbert, Paul, 1951 June 20– author. Title: Human nature and suffering / Paul Gilbert. Description: Classic edition. | Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2017. Identifiers: LCCN 2016003340 | ISBN 9781138954755 (hbk) | ISBN 9781138954762 (pbk) | ISBN 9781315564258 (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Mental illness—Etiology. | Psychobiology. | Sociobiology. | Suffering.Classification: LCC RC454.4 .G54 2017 | DDC 616.89—dc23 LC record available athttps://lccn.loc.gov/2016003340 ISBN: 978-1-138-95475-5 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-95476-2 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-56425-8 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman by Apex CoVantage, LLC

To June with love and immense gratitude for without you this would not have been possible

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

| Foreword | xi | |

|---|---|---|

| Acknowledgements | xv | |

| Introduction to the Classic Edition | xviii | |

| 1 | Introduction and overview | 1 |

| Outline 4 | ||

| 2 | A legacy from the past: the role of human nature | 6 |

| Historical background 6 | ||

| Evolution in the social context 10 | ||

| Evolution of biosocial goals and social strategies 15 | ||

| Biosocial goals 18 | ||

| A rough classifi cation 24 | ||

| Models for the interaction of cognition, behaviour and affect 30 |

||

| Concluding comments 33 | ||

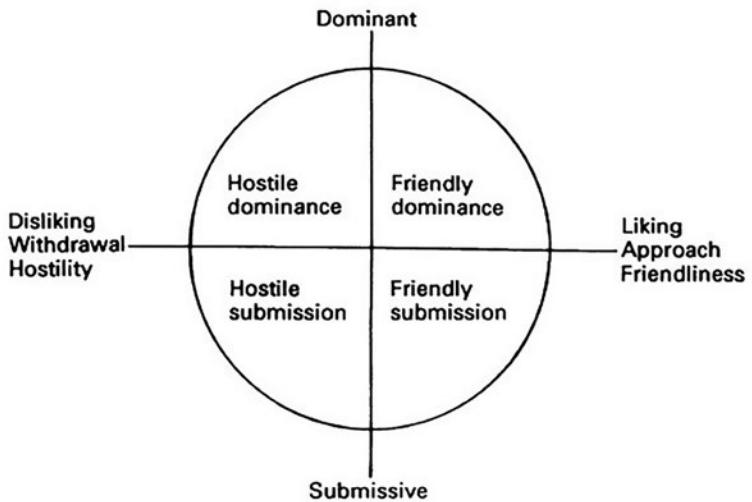

| 3 | The mapping of human nature | 36 |

| Jung’s theory of archetypes 36 | ||

| Ethological approaches to human nature 41 | ||

| The evolution of social roles 56 | ||

| Interpersonal approaches to human nature 59 | ||

| The cognitive approach 71 | ||

| Concluding comments 73 | ||

| 4 | The psychobiology of some basic mechanisms | 77 |

| Defence 78 | ||

| Safety 82 | ||

| The neurobiology of go–stop processes 84 | ||

| Neuropsychological aspects of defence and safety 91 | ||

| Concluding comments 96 |

viii Contents

| 5 | The psychobiology of peripheral systems | 99 |

|---|---|---|

| The endocrinology of defensive go states 99 | ||

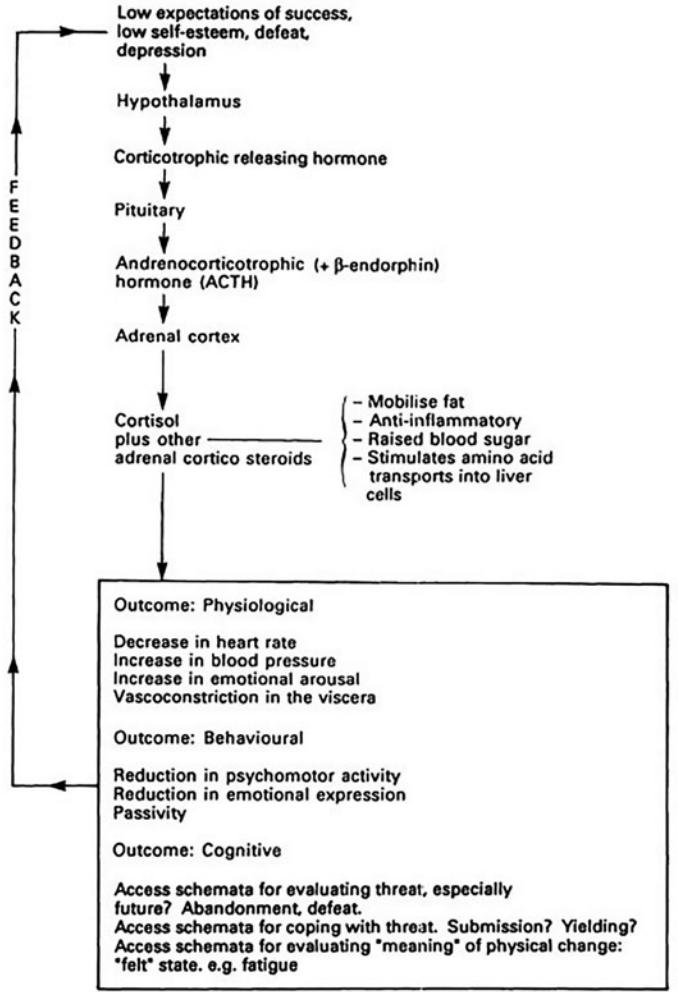

| Defensive stop states 102 | ||

| The psychobiology of changing states 110 | ||

| Concluding comments and the defensive drift hypothesis 113 | ||

| 6 | Care eliciting and attachment strategies | 117 |

| Attachment theory 117 | ||

| The importance of the infant’s experience of mediators 121 | ||

| The psychobiology of separation 126 | ||

| Confl ict in early relationships 133 | ||

| Concluding comments 134 | ||

| 7 | Care eliciting and theories of psychopathology | 138 |

| Early interactions with mediators 138 | ||

| Theories of vulnerability 144 | ||

| Care eliciting and psychopathology 148 | ||

| Developmental issues revisited 153 | ||

| The relationship of personality disorder to depression and anxiety 156 |

||

| Concluding comments 159 | ||

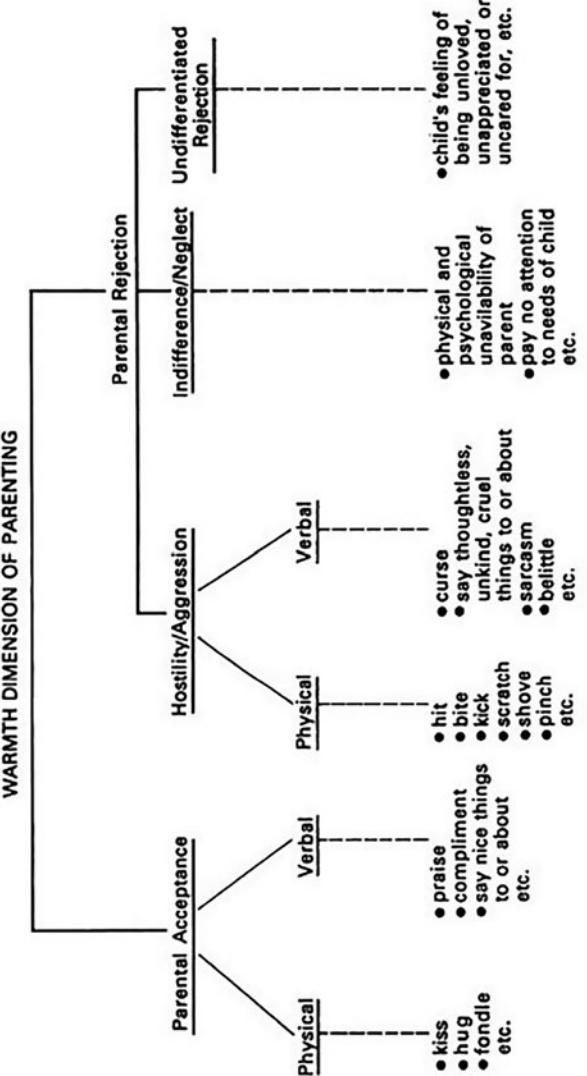

| 8 | Care giving and nurturance | 162 |

| Dimensions of care giving 162 | ||

| Evolution 168 | ||

| Affects related to care giving 172 | ||

| Psychotherapeutic points 176 | ||

| Concluding comments 180 | ||

| 9 | Disorders of care giving | 183 |

| Child–adult interactions 183 | ||

| Adult–adult relationships 192 | ||

| Concluding comments 195 | ||

| 10 | Co-operation | 198 |

| The importance of human co-operativeness 198 | ||

| Evolution 201 | ||

| Issues in co-operative relationships 203 | ||

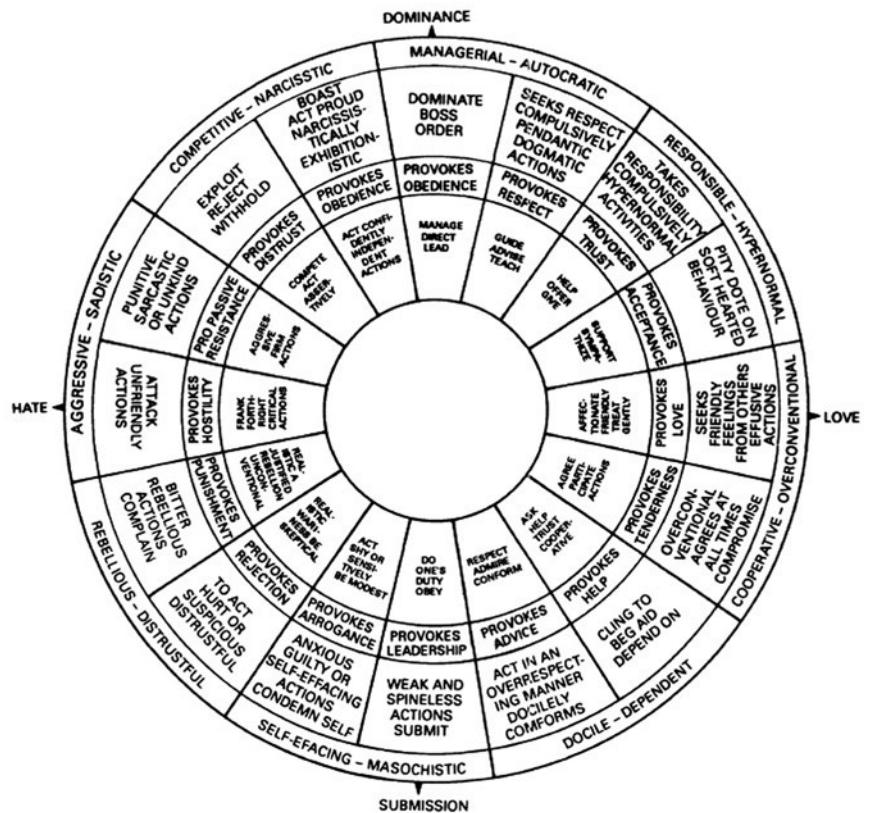

| Transaction in interpersonal relationships 216 | ||

| Concluding comments: co-operating versus competing 221 |

| 11 | Co-operation: some blocks and pathologies | 225 |

|---|---|---|

| Deception 226 | ||

| Guilt 235 | ||

| The relationship of guilt to shame 243 | ||

| Belief systems derived from co-operation | ||

| and reciprocal altruism 248 | ||

| Concluding comments 251 | ||

| 12 | Competition: status, power and dominance | 256 |

| Status 257 | ||

| Power and dominance 261 | ||

| Submission 268 | ||

| The psychobiology of status, power and dominance 271 | ||

| Gender: status, dominance and power 275 | ||

| Competition and sibling rivalry 281 | ||

| Concluding comments 284 | ||

| 13 | Some psychopathologies of status, power and dominance | 289 |

| Theories of psychopathology 289 | ||

| Type A personality 295 | ||

| Narcissistic personality disorder 301 | ||

| Concluding comments 308 | ||

| 14 | Beyond the power of reason | 312 |

| Social mentalities 312 | ||

| The self 322 | ||

| The mind as a system 332 | ||

| Psychotherapy implications 334 | ||

| Concluding comments 339 | ||

| 15 | Conclusions and refl ections | 341 |

| An overview 341 | ||

| Personal refl ections 344 | ||

| References | 352 | |

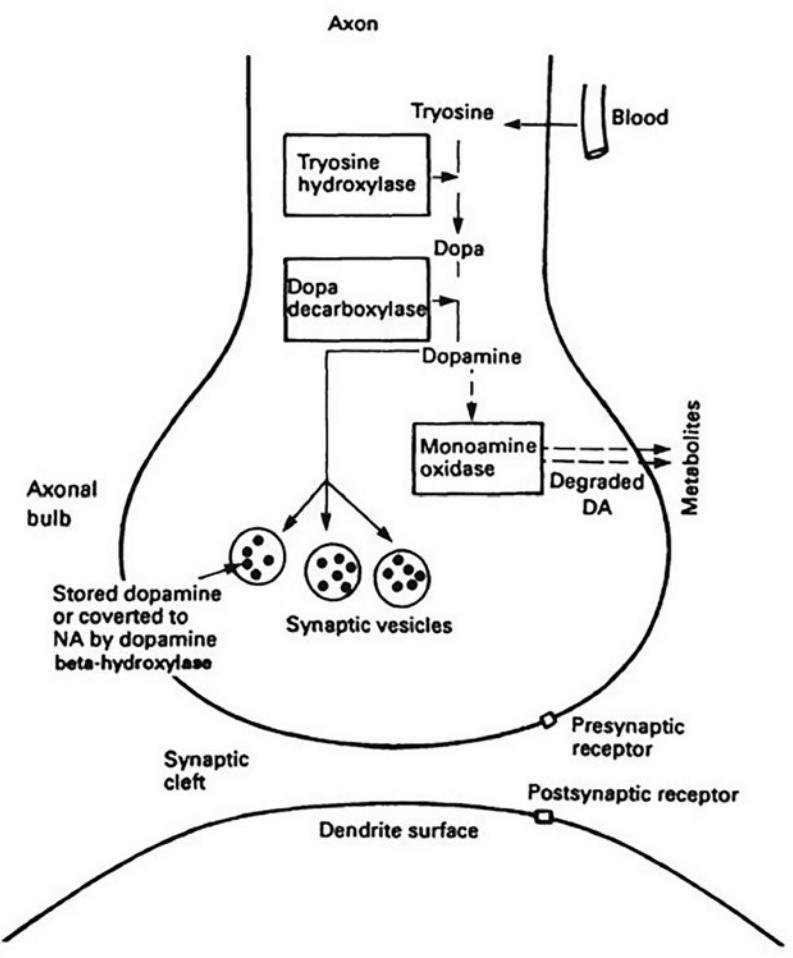

| Appendix 1 | 375 | |

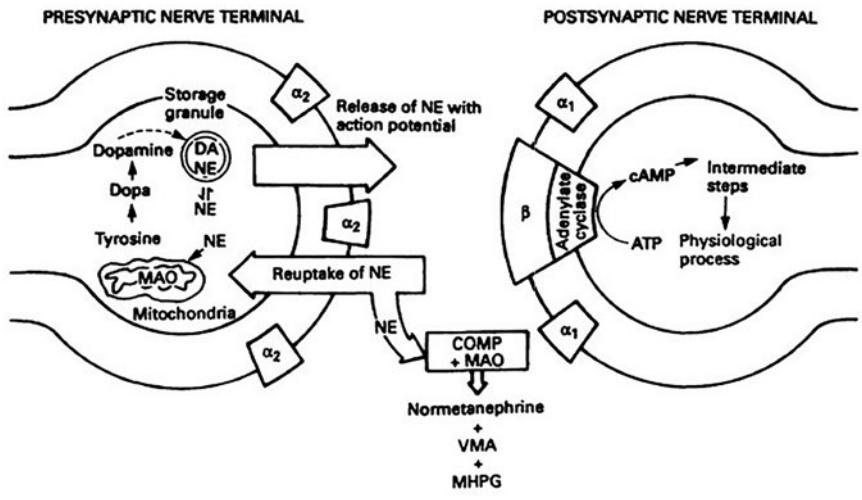

| The monoamine system 375 | ||

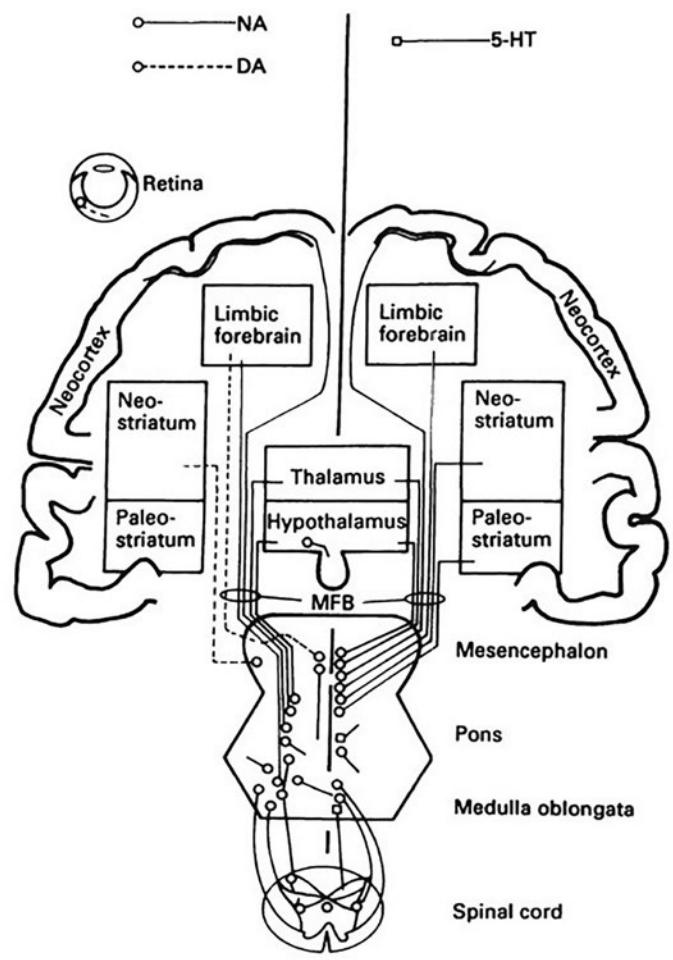

| The distribution of monoamine pathways 379 | ||

| Early neurochemical insights 379 | ||

| Current ideas on neurobiological mechanisms 381 | ||

| Appendix 2 | 383 |

|---|---|

| Homeostasis and beyond 383 | |

| Oscillating systems within the central nervous system 384 | |

| The psychobiology of ecological and climatic variation 386 | |

| Internal oscillators 389 | |

| Author index | 393 |

| Subject index | 401 |

Foreword

Towards a basic science of the clinical mental sciences

Clinical work proceeds best if guided by clarity in the clinician’s mind about normal processes that would have existed if something hadn’t gone wrong. We require a basic science of these processes as well as their correlated pathologies for functioning best with our patients and clients. Such knowledge orients the participants, provides rationale for procedures, gives direction and purpose for the exchanges thereby countering demoralisation, and enhances the “meaningmaking” for which we, as living creatures, possess innate neural mechanisms and, as humans, have particularly well-developed talents. We need a guiding framework formed not idiosyncratically and perhaps on the spot, but stemming from consensually derived concepts and procedures, and critical assessment of the data. We need a science, in short, that renders our helpees less at risk from our individual ignorance and personally derived communicative trends, some of which may indeed be helpful, while others may not. We need to be “mediators”, to use another term of Paul Gilbert’s with which you will become acquainted, providing these “sufferers” with mediation between them and the outside world of accumulated, systematic and valid – meaning useful – information about their complicated psychologies and psychotherapeutic experiences.

Development of such a basic science for the clinician in the mental illness and mental distress arenas comes with diffi culty. Models for such disciplined collections of information stem from domains that often seem remote from clinical work with the psyche. For physician members of these clinical areas (such as myself) the functional pathology course in medical school provided this type of model. I learned there that disease in medicine results when this or that tube is blocked or ruptured, when supplies consequently don’t get to an area, or waste accumulates or pressure builds or other assorted regulated functions go awry and can’t get easily realigned. What the patient says and exhibits is correlated with what the pathologist describes after biopsy or death, the radiologist suggests from computerised tomographic or magnetic resonancy outputs, or the chemical laboratory indicates from quantifi ed blood and urine constituents.

The clinical mental sciences don’t yet have such a model implemented although many would like to see it formulated as soon as possible. Thus, the dexamethasone suppression test was fashionable for several years in psychiatry, imaging techniques are seen as popular “cutting edge” potential diagnostic tools for mental disorders, and DSM-III (DSM-IIIR) has gained considerable ascendency as a tool for clinicians despite its empirical origins, seemingly atheoretical.

Actually, there have been problems with the rigorous implementation of such “basic sciences” within general medicine to which we should pay attention in our (as yet) less-developed science. Though the prefi x of “psych-” may not apply to those specialties dealing with diseases of the liver, heart or bone, patients with these disorders possess psyches still. To the extent that they become active receivers of information about the etiopathophysiology of their condition and “cooperate” or “collaborate” with the “guidance” that the clinician provides, things may go fi ne. But to the extent that the situation is less clear than some ideal-typical model of their condition, that their psyche contributes to the complaint or the behaviour, that demoralisation persists, that the person feels uncared for, that the clinician experiences the person to be a “bad patient” – to these extents, the medical basic science has failed; complete models of the illness and of the person’s distress have not yet been provided. Basic science knowledge limited to cellularmolecular referents insuffi ciently orients the participants, rationale for procedures attenuates, direction and purpose for clinician-potential helpee-exchanges goes astray, and demoralisation piles up. This helps explain the reason that patients have complained that US medicine (for example) has become dehumanised and that large-scale movements toward “primary care” medicine have been underway for several decades. They reject Shively’s “Damn It” differential (1987, p.449):

If it’s not Degenerative Anomalous Metabolically imbalanced Neoplastic Infectious or Traumatic Then it’s either healthy or dead.

How is it then, if what the patient feels is so important, that the psyche component of human suffering has counted for so much less than the cellular correlates of physical disarray? Part of it stems from all of us being experts. Each of us has felt distress as a part of the human condition. No-one has been exempted from human nature and the animal nature that gave rise to our humanness. Any of us snort sceptically as we hear of the experts giving contradictory evidence in courts of law, seemingly dependent upon which side is paying the fee? If the topic of psychopathology is broad, conceptualisations of the normal psyche and the numerous facets of brain function related to it range much more widely yet, as far as the eye can see. Daily we read about the meaning-making of psychologists, historians, philosophers, anthropologists, religious leaders, politicians, archeologists, administrators, novelists, poets, painters, psychoanalysts, sociologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, epidemiologists, public opinion pollsters, journalists and whole varieties of others who consider the human condition in the pages of books, journals, newsletters, magazines, newspapers, radio, television and notices posted upon campus trees. Each of us feeling equal claim to personal experience feels expert. The Greek historian Thucydides stated that “Of the Gods we believe, and of men we know, that by a necessary law of their nature they rule whenever they can.” Nowhere is this more the case than with the informational “territories” of human nature.

And in this lies part of the problem with our basic science and why the pathophysiologic model provided by organ pathology remains attractive: The microscope and its successors constitute arbiters, deciders, about who will rule in this opinion-making and theory-deciding and on what basis. Concrete evidence should decide not whose basic science will prevail but how an eventual comprehensive discipline will guide the clinical behaviours of most psyche-specialists – whatever the specifi c designation of the individual practitioner. Of course, whatever we are called, who among us dislikes being called an expert? The early Greeks in their numerous city-states struggled with the concept of the rule by law rather than through battle or under the tyranny of single individuals. They institutionalised cooperation and rule of the many rather of the individual or group that somehow triumphs. Our desire for a basic science to guide our work is parallel. Such discipline is assisted by this book, as Paul Gilbert mediates among the numerous citystates we inhabit. And assists our puzzled consumers in a media-driven culture trying to decipher varied claims of expertise.

As you will see in reading Human Nature and Suffering , Paul Gilbert has a fi tting defi nition for expert: “When a therapist was once called an ‘expert’ on human problems, he responded”Well, ‘x’ is an unknown quantity, and ‘spurt’ is a drip under pressure.” This sense of perspective guides his writing. Gilbert recognises clearly the interim nature of his presentation (and at the same time comments wryly on the multiple starts that so many have made in trying to conceptualise the fi eld). Rather, this is a broadly informed, comprehensively viewed perspective of our budding science. He is respectful of its varied subcomponents. But most importantly, he writes from the perspective of one who deals immediately, daily and compassionately with suffering human beings. While not over-awed by the microscope and its instrumental relatives in providing information, he respects them greatly. Perhaps his early training as an economist helped in his unusual sense of overview and in knowing the importance of general laws as guides to behaviour. Most of all, however, his training as a cognitive psychotherapist seems to have enhanced his regular exercise of meaning-making not only for the clients or patients in his consulting room, but for those of us who would be better “psyche-specialists” and who require an ever-improving basic science to guide us ever more precisely and care-fully. Dr Gilbert orients us to things both that we do know and that we need yet to learn, improves our rationale for a variety of our procedures, and directs and gives purpose to not only our direct clinical work but to our reading and to our collection of new information. Reading this book will acquaint one with an exciting “meaning-making” experience.

Russell Gardner, Jr. University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas

References

Shively, M.J. (1987). The “damn it” differential. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine . 30 , 449.

Thucydides (1910). (Trans.). History of the Pelopennesian War . Crawley, London and Toronto: J.M. Dent and Sons Ltd. (p.397)

Acknowledgements

A book of this form has been in my mind for a number of years. It is not until one sets for oneself the task of producing it that the fragmented themes and half understood ideas become coherent and start to make sense. I cannot claim much originality here since, as the reader will discover, much of what follows is a tapestry woven from the work and ideas of many. On my journey of articulating a scheme of human nature which underpins suffering, many people have given freely of their time and knowledge. They have guided me away from the darkness and the ridiculous and unreserved thanks goes out to them.

John Teasdale, Chris Brewin, Meinrad Perrez, Shirley Reynolds and Shirley Fisher have commented most helpfully on the various ideas and drafts. Thanks also to Peter Trower for his immense support and for pointing out all kinds of unnoticed implications. Tim Beck gave freely of his time when in England and also read some sections and wrote letters covering important points. Special thanks go to Russell Gardner for my early introduction to the importance of evolved social roles. Russell not only read various sections but wrote many letters trying to clarify my misty understanding of these matters. John Price commented helpfully on an earlier version and saved me from some serious errors. Special thanks go to Michael Chance who has tried (I hope reasonably successfully) to educate me in ethology and has signifi cantly infl uenced my ideas on social behaviour and the formation of human mentalities. He also read various chapters and was painstaking in his reviews and comments. Any errors of understanding, however, obviously lie at my door alone.

In my work environment there would have been little insight without the sharing of experience that many patients have provided. Their education is beyond repayment. Thanks also to Bill Hughes, a most valuable and supportive colleague of analytic persuasion and insight. Support also came from Catherine Lawrence and Chris Reynolds and more recently in Derby Chris Gillespie. My close friend, Elspeth McAdam has not only been her usual encouraging and supportive self, commenting and inspiring, but has had a profound infl uence on the tones and textures of my thinking with her knowledge of Maturana and systems analysis. Regretfully, the need for editing loses some of that sophistication. Thanks also to Brigitte Cole for her outstanding library services and making it possible to survey a wide literature. Also thanks must go to the energetic helpfulness at LEA, especially Michael Forster, Rohays Perry and Sue Wiszniewska.

The wives of those who choose to write often, for long hours, carry a heavy burden, and deepest appreciation and love go to Jean for the tea and empathy; and for understanding some of my ridiculous reasons for wanting to write; for help with the references, the checking and the sharing and for helping me to let go. Moveover, for allowing experiences of a deeper nature. The love of my children, Hannah and James, has also been inspirational. Thanks for teaching me how to be young again and that monsters, hide and seek and the Faraway Tree really are great fun. And last, but not least, thanks to my sister June. When she discovered my plans for the book, she immediately offered to type it on her wordprocessor. Neither of us realised at the time what this would entail. Over and over again, work was returned for re-editing and re-typing and June gave freely of her time and energy. To her I owe a great debt.

I have no doubt that science is the way out of darkness, yet to help us, science must not be a competitive enterprise but a co-operative one. It requires the generation of alternatives from which to choose and test; it requires cross fertilisation of ideas and it requires humans to think creatively and to contribute to the process of the application of knowledge. Whenever one paradigm is competitively defended, it inevitably leads to stagnation. Science requires us to be compassionately sceptical, to encourage each other to take part in the journey of understanding, to be ambitious in what we seek but cautious in what we affi rm; for it is not the mountain in the distance but the rock at our feet that will trip us up. This book is ambitious, but science is no respecter of ambition. There are still many unknowns, errors and falsehoods to be revealed.

All reasonable effort has been made to identify the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this volume. If the editor has inadvertently failed to obtain permission, please contact the publisher so that the necessary arrangements may be made.

Man is not determinate, clearly defi ned once and for all; he is something in process of development, and experiment, an intimation of the future, the quest and yearning of nature for new forms and new possibilities.

Herman Hesse: Refl ections

Introduction to the Classic Edition Foreward, reflection and update

I’m delighted that Routledge has decided to reissue Human Nature and Suffering ( HN&S ) (1989). This book took me six years to write and was the grounding for a lot of what emerged subsequently, including the development of compassion focused therapy (Gilbert 2000; 2010). I was also honoured when Dr Fraser Watts, then President of the British Psychological Society, having read the book, invited me to apply for a fellowship of the society. That was one of the great joys of my professional career.

The journey towards HN&S was seeded long ago. As a late teenager and young man I became fascinated by Jung’s concepts of archetypes, the evolution story and the fact that we humans are part of the fl ow of life. We are a species amongst many billions of others past and present, becoming what we are because of the struggles of reproduction and survival. Our bodies and brains are built by our genes and are shaped by our social life histories (Slavich and Cole 2013). Our capacities for anger, anxiety, love and hate arise from evolved brain systems. We choose very little of the way we experience ourselves and the world. Both Freud and Jung, indeed the whole early psychodynamic movement, thought they were working out the ways in which our evolved natures, with their different motives for sex and power, operate through our newly evolved, self-aware and culturecreating competencies. At the heart of this movement was the idea of the human mind as one of multiple motives, desires, emotions and memories, derived for earlier epochs, that could and often did confl ict. Indeed, by 1986 prominent psychologists like Robert Ornstein were arguing that:

The long progression in our self-understanding has been from a simple and usually “intellectual” view to the view that the mind is a mixed structure, for it contains a complex set of “talents,” “modules” and “policies” within. . . . All these general components of the mind can act independently of each other, they may well have different priorities.

The discovery of increased complexity and differentiation has occurred in many different areas of research. . . ., in the study of brain functions and localisation; in the conceptions of the nature of intelligence; in personality testing; and in theories of the general characteristics of the mind.

And even in standard undergraduate textbooks, this idea of the multiplicity and inherent confl icts of mind was well recognised. In 1992 Coon opened with:

You are a universe, a collection of worlds within worlds. Your brain is possibly the most complicated and amazing device in existence. Through its action you are capable of music, art, science, and war. Your potential for love and compassion coexists with your potential for aggression, hatred . . . murder.

(p.1)

The importance of motivational confl icts was also prevalent in behavioural work reaching back to Pavlov and the concept of experiential neurosis. Early cognitive therapists such as Beck also had an interest in the evolutionary basis of mind and psychopathology. In Beck et al’s. (1985) classic book on anxiety, the authors spent the fi rst third of the book discussing the evolutionary mechanisms upon which cognitive processes operate, although they did not articulate the issue of motivational and emotional confl icts that can be unconscious (Huang and Bargh 2014). Nonetheless, during the 70s, and 80s and even more so now, some schools of psychotherapy have been moving away from a focus on how evolution shaped the mind, particularly its confl ictual motivational and emotional nature. Also absent is that, as an evolved being, we have emotional needs. There are those Bowlby (1969) noted for security, care and affection, and if these aren’t met, particularly early in life, then the brain is affected; and we now know so are genes (Slavich and Cole 2013). We can’t learn to speak unless others speak to us, and our capacities for empathy can’t develop unless we experience the minds of others in a certain way. We are a very socially needy species; we need the status to feel valued included and connected, rather than marginalised and excluded.

Despite early cognitive interest in evolution, this did not infl uence the development of therapy. Beck was clear that he derived his therapy from clinical observations of “streams of thinking” that individuals could capture/learn to observe, refl ect on and learn to alter. Albert Ellis, another leader in the cognitive movement, was also clear that his approach was based on older philosophical concepts, especially the Stoics. His focus was on reasoning and self-directed behaviours as mechanisms for understanding emotion and emotion regulation, rather than psychological science of say attachment and moral development, social contextualism or evolved physiological mechanisms and their constraints and trade-offs. This was also a time of computers and artifi cial intelligence, with metaphors and terms like “information processing” used to imply “cognition”. Unfortunately, information processing can be an unhelpful term, because computers are information processing devices, as is our DNA, but these don’t have “cognitions” or “thoughts” in a meaningful sense. So while, of course, the human brain is an information processing system par excellence, information processing should not be equated with “cognition” and especially conscious cognition or reasoning – which is a very special kind of processing.

Though the cognitive movement was and is a major advance, and I began my therapuetic life here, I was always attracted to evolutionary psychology, which, during the 70s and 80s, was exploring some of the serious problems we have with the way the human brain has evolved (Bailey, 1989; Gilbert 1998; Gilbert and Bailey 2000). As Ornstein (1986) indicated so well, thinking was emerging around the idea that we may have specialised processing systems to do specifi c jobs. These include mechanisms for language acquisition, attachment, sexual behaviour, caring behaviour and competitive behaviour. Crucially, these various psychological processes could be seen as modular (Gazzaniga 1989); that is they could function independently of other modules in a way that I called “encapsulated” (see Chapter 14 , ‘Beyond the Power of Reason’). Encapsulation wasn’t just rooted in biological constraints, but could also arise as a process of learning; people could dissociate due to trauma or fail to integrate certain experiences, so they remained split off and literally encapsulated. Part of therapy is creating the conditions for increased awareness of these aspects of the self and their (safe) integration.

My fi rst book was called Depression: From Psychology to Brain State (1984). In it, I started to address evolutionary issues. Doing a PhD on an MRC unit in Edinburgh in the 1970s and surrounded by (friendly) biologically orientated psychiatrists, I became very keen on discussing how social and psychological processes could have major impacts on physiological systems; it was always a two-way street. They would talk to me about serotonin receptors and I would talk to them about the impact of helplessness on those receptors. In Depression , I tried to make the argument that we can understand depression against a backdrop of the evolved motivational and emotional infrastructures upon which our “psychology” operates. HN&S was an effort to develop these ideas further, not just for depression but also to try to build a model of mind that could relate human suffering (and mental health diffi culties) to processes arising from the evolution of our brains. Basically human life is (as the Buddha also taught) one of intense suffering a lot of the time (Gilbert 2009); hence, the somewhat grandiose title.

As I was starting to write HN&S , I developed some important mentoring friendships. One was with Anthony Stevens a well-recognised Jungian therapist who was also interested in linking Jung’s idea to modern evolution theory and attachment theory (Stevens 1982). John Price another evolutionary theorist who helped me focus on social rank and social competition as a separate motivational system to that of attachment, became a good friend too (Price et al. 1994). In addition, Russell Gardner, a professor of Psychiatry in Texas, shared generously his developing ideas about social communicative states that he called PSALICs. You will see these discussed in Chapter 3 – all too briefl y I now realise. He wrote a more developed paper for me in a special edition of The British Journal of Medical Psychology (Gardner 1998). So the 80s was an opportunity for a young man like me to talk to many colleagues and mentors, and the ideas I developed then were very much refl ections of some of those conversations, with much gratitude for the sharing of their wisdoms. My idea was that we could consider archetypes in terms of social mentalities, where a social mentality was a social motivation system with processing competencies that guided animals to seek out and then to “know” what kind of relationship they are in (say caring, sexual or competitive) and thus orientate them to behave accordingly, in moment-by-moment interactions played out or fantasized as interactional dances. Again Chapter 14 articulates this. In this way we could root archetypes in modern motivation and signal detection theory. So in HN&S you will see how I tried to do that.

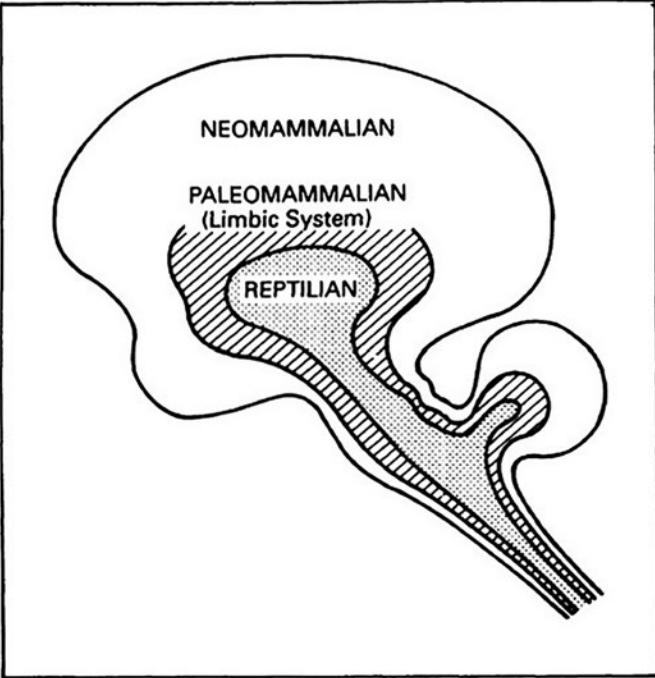

When HN&S was fi rst published, we obviously knew rather less than we do now about the fact that we have competencies and motives that stretch way back to our reptilian ancestry (Bailey 1989); well, actually, a key ancestor of ours was a turtle. My wife says I can still act like one! Our reptilian ancestors evolved brains capable of food seeking, self-defence, territoriality, status-seeking, sexual pursuits and living together in proximity, or as some say, the four F’s : feeding, fi ghting, fl eeing and intimacies. The brain mechanisms underpinning these life tasks are phylogenetically well conserved. The evolution of warm-blooded mammals brought into the world motives, emotions and competencies supporting live birth, kin-caring and alliancebuilding. Mammals carry forward older reptilian motives and emotions (and the four F’s ) but in addition evolve certain prosocial motives, emotions and competencies, particularly with the formation of caring for offspring, attachment and alliance formation. Motives for caring for and responding to being cared for require brains and bodies that create the physiological infrastructures for mammals to be sensitive and competent performers of different social roles (e.g., as parents and infants). These are discussed in Chapters 6 through 9 (see also, Gilbert 2013). In addition, the mammalian evolutionary process laid the foundations for the evolution of affi liative motives and competencies for grooming, support, sharing, co-operation and a whole range of other prosocial motives and competencies (Dunbar 2010). In HN&S I brought these under the general concept of co-operation ( Chapters 10 and 11 ). One of the things I would change now is to highlight the fact that guilt is very different from shame in terms of the social mentalities that underpin them. Guilt is linked to care-focused motives and harm avoidance/repair, whereas shame is status regulation, reputations, and self-evaluation (Gilbert 2007 ). In addition, of course, is the (older) important social mentalities that allow us to compete in the world and engage in the power dynamics and struggles for resources (where supportive relationships are key resources), survival and the competitive, confl ictual and sexual dynamics of life. These are discussed in Chapters 12 and 13 . It follows, then, that being able to quickly identify what role relationship one is in with another would be essential for the appropriate performance of that role and therefore its contribution to survival and reproduction. Hence, processing competencies attuned to specifi c social signals evolved to have specifi c impacts on physiological systems of interacting actors. So, for example, signals of sexual displays activate very different physiological systems than signals of distress that require caring, which in turn activate very different physiological systems than signals of friendship or threat dominant displays.

In those early days, then, evolutionary psychologists tended to think of four or fi ve basic motivational systems (Buss 1991). It’s these motivational systems that underpin our main social mentalities. The big fi ve included: caregiving, care eliciting/seeking, co-operating, competing and sexuality. Each of these requires different types of attentional focusing and cognitive processing, different types of physiological process and different types of behaviour. The key idea was to try to roughly articulate certain types of self–other role relationships that had an innate infrastructure underpinning them – and which would then mature and become patterned by life experiences. Table 1 gives a brief overview of the big fi ve, although I didn’t address sexuality much in HN&S . The last thirty years have seen major advances in this type of thinking (Huang and Bargh 2014).

To get a fl avour of social mentality theory, consider that competitive motives are linked to high self-monitoring, social comparison, drives to do as well as or better than others, need for achievement and desires to undermine competitors; aspects of narcissism are also linked to competitive motives. The threat system is attuned to vulnerability to shame, self-criticism, social rejection and put down, or simply being marginalised and ignored, along with narcissistic anger and/or depression and complex regulation of the dopamine system. In contrast, caring motives are linked to attention focused on the other, empathic engagement, desires to be helpful, desires to avoid causing harm and happiness in sharing and helping.

Obviously, things are more complex than simple encapsulated modules, because these motivational systems can become enmeshed and integrated too. For example, they could blend, and of course as noted above, they could confl ict with each other. They can also be context sensitive. So individuals who are highly competitive may be less likely to access caregiving and compassionate motives in certain contexts – and indeed there is now quite a lot of evidence that this is case (Van Kleef et al. 2008). Some individuals can be very competitive in one context (e.g., on the sports playing fi eld) but very caring in other contexts, such as family life. Other people

| Self as | Other as | Threats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care eliciting/ seeking |

Needing input from other(s): care, protection, safeness, reassurance, stimulation, guidance |

Source of: care, nurturance, protection, safeness, reassurance, stimulation, guidance |

Unavailability, withdrawn, withholding, exploitation, threatening, harmful |

| Care giving | Provider of: care, protection, safeness, reassurance, stimulation, guidance |

Recipient of: care, protection, safeness, reassurance, stimulation, guidance |

Overwhelmed, unable to provide, threat focused, guilt |

| Co-operation | Of valued other, sharing, appreciating, contributing, helping |

Valuing contribution, sharing, reciprocating, appreciating, affi liative |

Cheating, nonappreciating or reciprocating, rejecting/shaming |

| Competitive | Inferior/superior, more-less powerful, harmful/benevolent |

Inferior/superior, more-less powerful, harmful/benevolent |

Involuntary subordination, shame, marginalisation, abused |

| Sexual | Attractive/desirable | Attractive/desirable | Unattractive, rejecting the interest |

| Table 1 A brief guide to social mentalities |

|---|

| ——————————————— |

can be very competitive and tyrannical within the family yet submissive outside the family. Individuals can have a power relationship with carers (parents) and get caught in resentful or fearful subordination strategies. They can be very frightened to acknowledge hostility or rage at parents for example (à la Freud). Others can close out care-seeking behaviours in favour of compulsive self-reliance and dominant control. Sometimes psychotherapy requires not only a toning down of some motives and strategies but a toning up of others. Indeed, I discussed these issues with Anthony Stevens (who thought this was exactly Jung’s view) and also Tim Beck during the 1980s. Beck, Freeman and Associates (1990) also talked about the importance of personality disorders in terms of the under- and over-development of certain evolved strategies and motives. So there was a zeitgeist for these ways of thinking in those days that is sometimes forgotten now.

What was crucial to Jung’s view however, and was not captured well enough in HN&S , is that these different motives mature, blend, integrate and can contribute to “individuation” (Stevens 1982). The human capacity for integrating different motives, emotions and dispositions becomes important for mental health and wisdom in contrast to a series of disconnected, competing and at times unconscious processes (Huang and Bargh 2014). Today we see the capacity for increasing awareness of inner states, our motives and drivers, along with competencies for refl ective functioning, as central to the process of integration and individuation (Gildersleeve 2015). Compassionate self-training seeks to support integrative functioning (Gilbert 2009, 2010; Gilbert and Choden 2013)

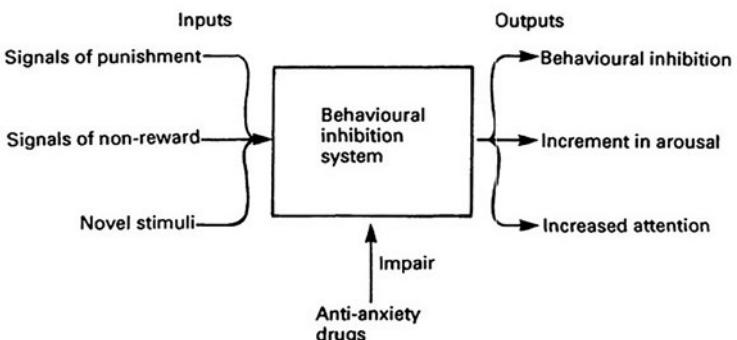

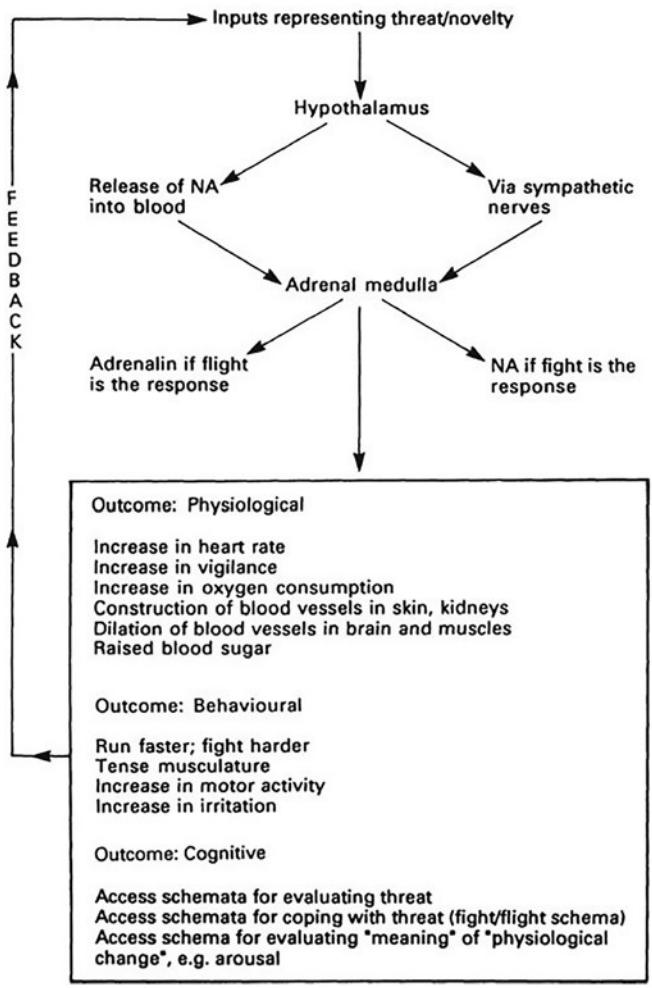

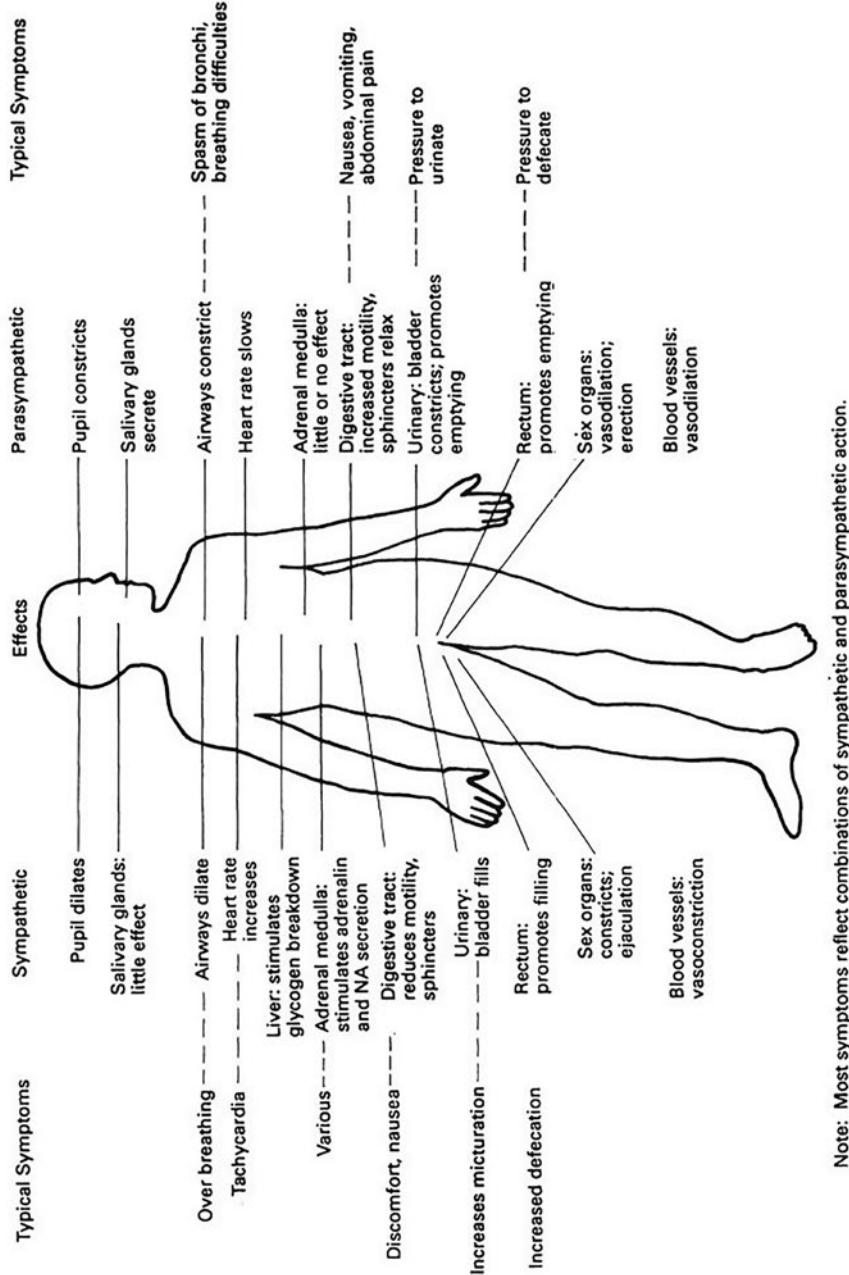

Emotions

Just as motives can be understood from an evolutionary functional analysis point of view, so can emotions. For a long time psychological research made it clear that we (like other animals) have (at least) two different types of emotion systems – loosely noted for punishment and rewards (Gilbert 1993). First are emotions that are associated with threat detection and defence; second are emotions that can arise when animals are relatively safe from risk of harm, and are able to seek out rewards, are explorative and are acquiring and enjoying resources. The way in which threat and positive affect systems work, and how they link to “stop and go” behavioural systems is outlined in Chapters 4 and 5 . It’s interesting to see how things have changed in this area since those chapters were written (Gilbert 2009).

We have known for many years that the threat system is organised to be “better safe than sorry”, sensitive to threats to whatever motivational system is operating, but also survival and injury threats. We also know that there is a hierarchy of threats. For example, if one is out walking with others but feeling socially anxious and then hears the sound of a lion nearby, social anxiety has to be quickly replaced by predator threat anxiety and the need to run. Indeed, this fundamental “hierarchy of threats” turns up in clinical work all the time. Humans can also feel threatened by internal cues and stimuli. Individuals can be fearful of their anger for example if it risks rejection or counterattack. Classical conditioning theory was very clear that one physiological state could be conditioned to another and block it. So, for example, a bell might be associated with food and become a conditioned stimulus for saliva, but if the bell is also paired with a punishment (mild electric shock), this causes confl ict and seriously disrupts the animal response systems, causing high distress arousal and disorganised states and suppression of the salivation response. Compassion focused therapy was to go on and use, and root itself heavily in, classical conditioning concepts like this (Gilbert 2010). Individuals may become unaware of the cues that trigger anger because anger is conditioned to anxiety (as in the case of a child who is repeatedly punished for being angry or expressing emotion). Awareness of, and sensitivity to, addressing the stimuli that triggered anger are suppressed in favour of addressing the threat (punishment) that the (expression of) anger can cause. Clearly, even if one cannot process anger, anger can still be triggered, but one doesn’t know how to be assertive. The consequnce can be that one ends up feeling defenceless, out of control and in a submissive position, vulnerable to anxieties and depressions.

Threats can also knock out positive emotions because pursuing positive resources in the face of high threat is obviously maladaptive. This was to become a crucial issue in compassion focused therapy, because individuals who are threat dominant, self-critical and live life trying to stop bad things happening, often struggle with allowing and experiencing positive emotions, particularly affi liative emotions (Gilbert, McEwan, Matos, & Rivis 2011). The point here, though, is that rather than thinking of anxiety systems or anger systems I focused on the idea of a threat system “as a system”, because it’s the variety of the actual defences that links evolved threat detection responses to the human experience of emotion. Also, within the threat system there is a constant interplay of one defence response such as anger suppressing another such as anxiety. Indeed, I invited Keith Dixon (1998), a noted ethologist and researcher at the time, to write a paper on this for a special edition of The British Journal of Medical Psychology that I was editing. In HN&S I referred to threat processing as the defence system (Gilbert 1993, 2001).

One of the core issues I focused on was the fact that some responses to threat are active whereas others are passive . These are linked to different physiological systems. Fight and fl ight are obviously active whereas fainting and freezing are more passive. However, an important passive form of defence is the loss of positive emotion and explorative drive – the “stop moving, hide and hunker down” response. Beck et al. (1985) referred to this as demobilisation . Bowlby (1969) referred to it as despair states and learned helplessness. Seligman (1975) described it as a helplessness state. These states are associated with major changes in neurotransmitters, which can be conditioned, and are common with anhedonic types of depression. These defences are typical in situations where active defences are not going to work or could be dangerous, such as actively searching alone for a lost parent/caregiver, making one vulnerable to predation and dehydration, or coping with down-rank aggression (Gilbert 1992, 2006 ). Consequently, the “action” systems are switched off.

A second important emotional system relates to seeking out rewards and resources conducive to survival and reproduction. In order to do that, animals have to sense a degree of safety, because without that safety, such seeking behaviour would be (defensively) blocked. I was interested in the emotions that we can experience when we feel safe. While there is a menu of threat-based emotions (anger/fi ght, anxiety/fl ight, anxiety/freeze) is there also a menu of emotions and behavioural dispositions for when we feel safe (joyful, playful, excited, happy, contented, peaceful)? Again, it seems there is an active, energised and energising dimension of positive emotion, and a passive dimension to (what I called then) safety. So when we are active and safe, we can explore and enjoy exploring – running around and having a good time; whereas when we are safe and passive, we are more parasympathetic and in the rest and digest domain of safeness (Gilbert 1993).

You will notice I have used the word “safeness” here, because actually “safeness” is a better term than “safety”. The late ethologist Michael Chance read HN&S and suggested that safeness and safety are different. Safety is focused on becoming safe from threats. Safety focuses on stopping bad things happening , whereas states of safeness are linked to freedom to act. This seemed to me an important distinction but came some years after HN&S (Gilbert 1993, 2001). Certainly in therapy we have to make a distinction between the focus on preventing bad things from happening (where one defence can block another) in contrast to enjoying a sense of freedom and safeness. Freedom allows us to be active, have fun and be joyful. It also creates a secure base (in Bowlby’s terms) from which we may move out to explore more threatening things – gain confi dence and grow. Thus, the concept of feeling “safe enough to try”.

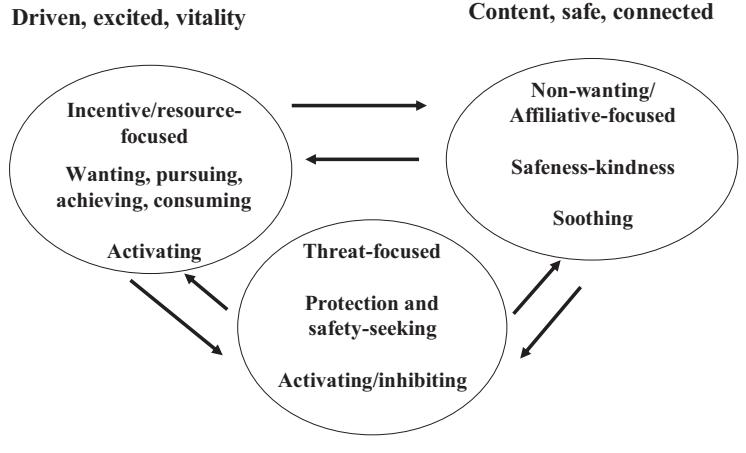

Today we can (based on evolutionary functional analysis) distinguish between three types of emotion regulation systems. This is guided by the work of Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky (2005), Ledoux (1998), Panksepp (2010) and Porges (2007). What has become clearer since HN&S was fi rst published is that positive affect has two very different types of evolutionary function and is experienced in two very different types of ways with very different impacts on the body. These emotion regulation systems are given in Figure 1:

- Threat and self-protection focused systems enables detecting, attending processing and responding to threats. There is a menu of threat-based emotions such as anger, anxiety and disgust, and a menu of defensive behaviours such as fi ght, fl ight, submission, freeze etc. Various subdivisions have been suggested by Panksepp (2010).

- Drive, seeking and acquisition focused system enables the paying of attention to and responding to stimuli indicating resources, and with some degree of “activation”, an experience of pleasure in pursuing and securing them.

- Contentment, soothing focused system enables a state of contentment, peacefulness and openness where individuals are not threat focused or seeking resources, but are satisfi ed. Also linked to feelings of well-being. This is linked to the parasympathetic system, which is sometimes called a “rest and digest” system.

Anger, anxiety, disgust

Figure 1 Three types of affect regulation system

From Gilbert (2009) The Compassionate Mind , with kind permission from Constable Robinson.

The evolution of social behaviour was to have a major regulatory impact on all of these systems. For example, threat systems can be stimulated by threats to others, particularly one’s own offspring, loved ones or allies; joy and excitement states can be stimulated by friends and the pleasure of doing things together; and importantly, soothing and calming can be generated by comfort, support and helpfulness. Indeed, a sense of social safeness is very important to well-being (Kelly et al. 2012).

In essence, we can separate out the passive and active elements of positive affect. The active elements are linked to drive and sympathetic arousal, and the more soothing sense of safeness is linked to the parasympathetic system, keeping in mind that the relationship between the two is complex.

The idea of there being two different types of positive emotion that are linked into active and passive and different degrees of sympathetic and parasympathetic arousal became very important and was to underpin compassion focused therapy (Gilbert 2000, 2010).

Compassion focused therapy notes that our drive emotions can be linked into safety-seeking strategies , where we are constantly trying to do things to stop bad things happening. We are rushing around doing this and that, and we can feel relief when we do those things, but they are not necessarily a source of joyfulness or freedom. We rush around at work not because it’s joyful necessarily, but because we need to keep our jobs and pay the mortgage. But there is also an active form of safeness that is pleasurable and allows us to be joyful, play and have fun, such as when we share jokes at a party of friends or go on holiday. This kind of safeness allows us to feel free to move, free to think, free to act. Safeness allows us to do things. The passive forms of safeness give rise to a sense of contentment, the ability for just being as opposed to doing – for resting. We can just “be” experiencing the present moment with out doing – although purposely focusing on the present moment is a form of doing in a way. What’s important about “safe” passive states is not only their “rest and digest” aspects, but also that when we are able to slow down a little, we bring the parasympathetic system online. This is associated with improved heart rate variability, which has a whole range of benefi cial health effects (Kemp and Quintana 2013; Porges 2007) and is associated with prosocial behaviour (Kogan et al. 2014). Heart rate variability also facilitates better frontal cortical functioning (Thayer et al. 2012). Human Nature and Suffering hinted at these points, as you will see, but was not able to articulate them as clearly as we can today with all of the new research.

Cognition

HN&S also touched on the nature and role of evolved human cognitive competencies, and their impact on suffering – and it is rather amazing, tragic and tricky (Sapolsky 1994). The fact is that about 2 million years ago our ancestors (probably beginning around the time of Homo erectus ) began to evolve a range of cognitive competencies such as language, imagination, systemic thinking, conscious awareness of self, self-identity formation and self-monitoring. Two million years is actually a short time for such major competencies to evolve, and one of the reasons for this runaway evolution is that these competencies – especially social intelligence – had huge advantages (Dunbar 2010). However, it is only in the last 10,000 years or so that these “intelligences” impacted and changed the world with the advent of agriculture, writing, culture and the sharing of knowledge. These cognitive systems also produced completely new ways for human benefi t but also for suffering to emerge. We literally “brought stimuli inside our own head”, responding to symbolic thoughts and images almost identically as if they were happening in the outside world. A moment’s refl ection will reveal that if we lie in bed imagining or rehearsing an argument we’ve had, it will stimulate anger physiological profi les, but these will be very different physiological patterns than if we, on purpose, choose to create a sexual fantasy. Back to social mentalities. What role are we in – or in this case imagining? The key here is that what comes into consciousness, either deliberately or not, and how we deal with that, can play our physiological systems – emotions and motives – like fi ngers on a piano.

Another example highlights how we can hold things in the mind, particularly things that have upset us. Imagine a zebra that escapes from a lion. It will quickly go back to the herd and graze, whereas humans are more likely to ruminate and imagine the worst: “Can you imagine if I’d been caught? Imagine what it would be like to be eaten alive!” And of course we can (under the direction of the threat system) anticipate the worst: “What if there are two lions tomorrow? What if I can’t get to the waterhole? What if my children wander out? What if . . . what if . . . what if . . .?” This is not deliberate recall, but once it enters the mind, it can get stuck there constantly fuelling threat processing and physiological activation. Another example is that we can go through a day where people are kind and helpful to us, but if we have an argument with somebody, then those kindly events are easily forgotten, and we ruminate on the one person who really annoyed us. Cognitive therapy has focused very clearly on this tendency to selectively abstract and focus on threatening things but hasn’t always articulated that this is how the threat actually works. It is not our fault that it does this. In fact, shortly after HN&S was published, a wonderful book by a Stanford primatologist (look him up on YouTube) came out with a book titled Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers in which he outlined how our newly evolved cognitive competencies and the cultures they have created combine to (potentially) drive us all crazy and make us sick.

So we now know that these ways of thinking play a really important role in the stimulation and maintenance of mental health problems. And of course there is a huge range of symbols that can stimulate anxiety, such as putting your hand in your pocket and fi nding that you have been robbed of your credit card or passport (credit cards and passports don’t exist in nature), or when someone you want to care for you forgets to send you a birthday card. It is their symbolic representation – the network of meanings that symbols are linked to – that links them to threat system; it is the implicational network that is crucial. It is the same with the self. As far as we know, animals don’t have a sense of self-identity or symbolic representations of themselves, but humans clearly do, which makes us vulnerable to shame on the one hand but also causes us to fi ercely defend our selfidentity on the other. Again it is the implications of certain kinds of judgement that are crucial, and of course at a deep level, it is the implications that are related to survival and reproduction opportunities/threat that are the most emotionally disturbing. For example, events that have implications for any form of social rejection in a desired relationship will have survival and reproductive implications – at least as far as brain processing considers them.

Self-monitoring is also a hugely important evolved competency for human mental functioning. No other animals, as far as we know, can monitor their heart rates and worry about dying, or monitor their emotions and worry about what they are feeling and fantasising. No other animal tries to monitor or anticipate what’s going on in the minds of others, or worries about being disliked or rejected – at least not in the detailed way humans can. Humans constantly self-monitor. While this has advantages, it is also a source for judgements and projections and can be a basis for our ongoing self-criticism.

And, of course, we are fantastically creative problem solvers and have developed culture, science and medicine. It has made us the dominant species, but this same brain, that is a creative developer of solutions, a bringer of medicines, can also develop hideous tortures and the most horrendous cruelties. Humans are amongst the cruellest of species that have existed on this planet – to ourselves, each other and animals. We must always remember that these recently evolved cognitive competencies come with trade-offs, as well as extraordinary and important responsibilities for insight into and regulation of our actions that humans still struggle to take. These new brain competencies are not the creators of emotions and motives that fl ow through the body; they are elaborators and conductors. They are not the orchestra; the actual orchestra is part of the evolved emotional motivational brain.

Learning how better to deal with the orchestra is part of the challenge of humanity. So clearly it’s the use of our intelligence that is going to help us to understand our own brains and begin to gain deeper insights into the nature of human suffering and generate solutions to it. We are a questioning, seeking, restless species and one of the questions all humans ask is: why do we suffer (Gilbert 2009)?

Summing up

Refl ecting back over 30 years, it is interesting how some things have changed and yet others remain the same. Our science of mind is clear that the human brain has some very serious diffi culties as a result of the way it evolved . It’s a tricky brain. The great thing about science is that we can study things as they really are, not just how they appear to be from the outside. As I often say to my students, “It is (y)our responsibility to try to help us understand humanity, the human mind, and the human predicament and the solutions for it; no one else is going to do it; not the physicists, nor the chemists; not the geologists, nor the farmers. Sometimes, physical scientists make fun of psychological science and see it as”not real” science – or sometimes call it soft science. But what many psychologists are concerned with now is to really root our understanding of psychological processes in the systems that give rise to them – the evolved and socially shaped body and brain.

The science of mind can dig deeply into the roots of our suffering and can recognise that the way we treat each other is one of its causes and cures; suffering is created between us, not just in us. The more we understand how this comes about (and of course it’s hardly a new insight), the more it becomes obvious how important it is to use our science to work out how to promote prosocial values and behaviours in our families, schools, workplaces, businesses and governments (Gilbert 2009). The most profoundly important challenge of this century is to promote human fl ourishing through prosocial behaviour and human compassion. Nearly three decades after the publication of Human Nature and Suffering , psychological science is taking the study of compassion and prosocial behaviour seriously, and understanding their fundamental importance in humanity’s future. For me, my personal journey into compassion focused therapy began more than 30 years ago here in a book called Human Nature and Suffering . I hope you enjoy revisiting this with me.

References

Bailey, K.G. (1989). Human paleopsychology. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum. Beck, A.T., Emery, G. & Greenberg, R.L. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive approach . New York: Basic Books .

- Beck, A.T., Freeman, A., & Associates. (1990). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders . New York: Guilford Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss , Vol. 1. London: Hogarth Press.

- Buss, D.M. (1991). Evolutionary personality psychology. Annual review of psychology , 42 , 459–491.

- Coon, D. (1992). Introduction to psychology: Exploration and application (6th edition). New York: West Publishing Company.

- Depue, R.A. & Morrone-Strupinsky, J.V. (2005). A neurobehavioral model of affi liative bonding. Behavioral and brain sciences, 28 , 313–395.

- Dixon A.K. (1998). Ethological strategies for defence in animals and humans: Their role in some psychiatric disorders. British journal of medical psychology, 71 , 417–445. Published online: 12 July 2011. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01001.x

- Dunbar, R.I.M. (2010). The social role of touch in humans and primates: Behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 34, 260–268. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.001

- Gardner, R. Jr (1998). The brain and communication are basic for clinical human sciences. British journal of medical psychology, 71 , 493–508.

- Gazzaniga, M.S. (1989). Organization of the human brain. Science, 245 , 947-952.

- Gilbert, P. (1984). Depression: From psychology to brain state . London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Gilbert, P. (1993). Defence and safety: Their function in social behaviour and psychopathology . British journal of clinical psychology, 32 , 131–153.

- Gilbert, P. (1998). Evolutionary psychopathology: Why isn’t the mind better designed than it is? British journal of medical psychology, 71 , 353–373.

- Gilbert, P. (1992). Depression: The evolution of powerlessness. London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Gilbert, P. (2000). Social mentalities: Internal “social” confl icts and the role of inner warmth and compassion in cognitive therapy. In P. Gilbert & K.G. Bailey (eds.), Genes on the couch: Explorations in evolutionary psychotherapy . Hove: Psychology Press.

- Gilbert, P. (2001). Evolutionary approaches to psychopathology: The role of natural defences. Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry, 35 , 17–27.

- Gilbert, P. (2006). Evolution and depression: Issues and implications (invited review). Psychological medicine, 36, 287–297.

- Gilbert, P. (2007). The evolution of shame as a marker for relationship security. In J.L. Tracy, R.W. Robins & J.P. Tangney (eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 283–309). New York: Guilford.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind: A new approach to the challenge of life. London: Constable & Robinson

- Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: The CBT distinctive features series . London: Routledge.

- Gilbert, P. (2013). Attachment theory and compassion focused therapy for depression. In A.N. Danquah & K. Berry (eds.), Attachment theory in adult mental health: A guide to clinical practice . London: Routledge.

- Gilbert, P. & Bailey K.G. (2000) Genes on the couch: Explorations in evolutionary psychotherapy . Hove: Psychology Press.

- Gilbert, P. & Choden. (2013). Mindful compassion . London: Constable Robinson.

- Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M. & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and psychotherapy, 84 , 239–255. doi:10.1348/147608310X526511

- Gildersleeve, M. (2015). Unconcealing Jung’s transcendent function with Heidegger. The humanistic psychologist, 43 , 297–309. doi:10.1080/08873267.2014.993074

- Huang, J.A. & Bargh, J.A. (2014). The selfi sh goal: Autonomously operating motivational structures as the proximate cause of human judgment and behavior. Brain and behavioral sciences, 37 , 121–175.

- Kelly, A.C., Zuroff, D.C., Leybman, M.J. & Gilbert, P. (2012). Social safeness, received social support, and maladjustment: Testing a tripartite model of affect regulation. Cognitive therapy and research, 36 , 815–826. doi:10.1007/s10608-011-9432

- Kemp, A.H. & Quintana, D.S. (2013). The relationship between mental and physical health: Insights from the study of heart rate variability. International journal of psychophysiology, 89 , 288–296.

- Kogan, A., Oveis, C., Carr, E.W., et al. (2014). Vagal activity is quadratically related to prosocial traits, prosocial emotions, and observer perceptions of prosociality. Journal of personality and social psychology . Advanced online publication.

- LeDoux, J. (1998). The emotional brain. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Ornstein, R. (1986). Multimind: A new way of looking at human beings . London: Macmillan.

- Panksepp. J. (2010). Affective neuroscience of the emotional BrainMind: Evolutionary perspectives and implications for understanding depression. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 12, 383–399.

- Porges, S.W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological psychology, 74 , 116–143.

- Price, J., Sloman, L., Gardner, R., Gilbert, P. & Rohde, P. (1994). The social competition hypothesis of depression. British journal of psychiatry, 164 , 309–315.

- Sapolsky, R.M. (1994). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: Guide to stress, stress-related disease and coping. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (1975). Helplessness: On depression development and death . San Francisco: Freeman & Co.

- Slavich, G.M. & Cole, S.W. (2013). The emerging fi eld of human social genomics. Psychological science . Advance online publication.

- Stevens, A. (1982). Archetype: A natural history of the self . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Thayer, J.F., Ahs, F., Fredrikson, M., Sollers, J.J. III, Wager, T.D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews , 36, 747–756.

- Van Kleef , G.A., Oveis, C., van der Lowe, I., LuoKogan, A., Goetz, J., & Keltner, D. (2008). Power, distress, and compassion: Turning a blind eye to the suffering of others. Psychological science, 19 , 12 1315–1322. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02241.

This page intentionally left blank

Introduction and overview

Despite a radically different view of human psychology than existed in Freud’s day, psychoanalytic theorising continues to exercise a powerful hold over western imagination. Why should this be? There appear to be many reasons, none of which necessarily tells us of the truth or falseness of psychoanalytic formulation. First, at least on the surface, it speaks to us in a familiar language; a language of description which resonates with the personal. We may experience symptoms and desires we cannot explain. We recognise the aggressive and vengeful in ourselves and also the desires to be approved of, loved and respected. Second, it places these personal propensities at its centre, to be explained systematically, and it attempts to provide answers to the contradictory and paradoxical. Third, while it speaks in terms of mental mechanisms as fragmented wishes, desires and fears, it nevertheless offers some possibility for coherence and union. Fourth, it offers a new principle of knowing, based on free association which requires the individual to suspend moral and logical reasoning.

Psychoanalytic theory in common with some philosophical forms of enquiry appeals to our sense of the mythic. We can analyse fi lms and books in terms of archetypal relations; e.g. the journey and trials of the hero, the search for truth, the fi ght between good and evil, the lost anima (animus) object, treachery, deceit and war. These are repetitious human themes of interaction. In these we fi nd mirrors to our own personal lives and those subjects and discourses revealed by the tellers of fi ction and myths. Perhaps, as some suggest, it was his talent for mythic story telling and literary style that made Freud so popular.

And yet for all this, it is becoming increasingly clear that the cure of suffering most often requires action. The behavioural and social learning sciences have impressed on us the vital importance of behavioural confrontation with the feared; the need to strengthen the will to act rather than the power of understanding or insight alone. Indeed, the latter may at times depend on the former. Despite powerful arguments (Wachtel 1977; Erdelyi 1985), these two procedures, the introspective free associative, revelatory and the behavioural are not easily married. Nevertheless, psychotherapeutic practice and theory are becoming more eclectic, trying to pin down the crucial elements that facilitate change (Karasu 1986; Beitman 1987).

2 Introduction and overview

At the time when psychoanalysis was getting bogged down in increasingly jargonistic complexities of the human psyche, and the refi ning of technique (which gradually evolved into increasing distance between patient and therapist) the behaviourists offered new, simpler and more scientifi cally verifi able explanations for suffering. In this sense the operant approach offered (at least superfi cially) a rebuke to individualism and pointed the fi nger at external contingencies. Behavioural therapists suggested that previous contingencies of reward and punishment could result in neurosis. For example, Ferster (1973) argued that the suppression of anger arose from a child’s early conditioning of external punitive consequences to assertive and aggressive behaviour. In other words, the child came to fear the consequences of its own assertive and aggressive behaviour. For these theorists, neurosis was not a thwarting of instinctual drives, but the consequences (usually) of a punitive environment. For them, there was no necessity to consider how a punitive environment interacted with an evolved system of varied mental structures, the activity of which was (presumed) mostly unconscious. Neitzche’s will to power and the existentialists’ will to meaning were rendered the products of personal environmental history.

No theory can be fully understood without recourse to its historical culture of embeddeness (Ellenberger 1970). It is from this source that any direction of enquiry must commence. There would have been little medieval philosophy, no St Augustine or Thomas Aquinas were it not for a set of religious and ethical premises set up by Christianity. Whereas some religious healers saw suffering as the result of transgression (Zilboorg and Henry 1941) Freud saw neurosis as the fear of transgression, the result of a submissive will, fearful of knowing and acknowledging. Thus, for Freud suffering arose from too much adherence to authority, rather than too little. Hence, in his day, Freud became the focus for the loss of prohibition, the liberation of the sexual, the release from guilt and the preference for knowing over ignorance, prejudice and obedience. Up until the 1930s the BBC banned the broadcasting of talks on psychoanalysis and the establishment continued to see sexual desires as needing to be tamed by punishment or cold showers. Homosexual acts were sins against God and worthy of punishment. The institutions of power and the continuance of the culture of command were the way of correct order.

But liberating or not, resonating or not and freeing or not, the psychoanalytic method of understanding the psyche has always been in doubt, and its treatment of suffering even more suspect. Maybe it was not free association and dream analysis or even “the knowing” that cured, but rather the relationship between therapist and patient. Maybe it was the recapture of a certain form of empathic intimacy that made the difference as Rogers, and later Kohut, were to argue. Maybe the Oedipus complex was rare or even irrelevant, as both Jung and Horney argued; and maybe we do not need to have much insight into the structures of mentality in order to work as therapists, as the behaviourists argued. What emerged was a schism between the observed, the pulse that psychoanalysis had put its fi nger on, and the theoretical monuments erected to explain it.

More recently through the work of Neisser (1967, 1976) the behaviourist hold over academic psychology has loosened. The result of this was called a cognitive revolution (Mahoney 1974, 1984). At the same time, new movements in psychotherapeutic endeavour have grown out of the post-behavioural and postegoanalytic period and are marked especially by the works of Beck and Ellis. The post-cognitive revolution has now given rise to a new theoretical paradigm called “cognitive constructionism”, and a recognition that cognition is a biological issue (Maturana 1983; Dell 1985: Mahoney and Gabriel 1987).

However we wish to plot the history of the last fi fty years, there seems to be an increasing wish to return to the grappling with the ageless questions of understanding human beings as coming into the world in states of preparation. What is born after nine months gestation is not a tabula rasa, but a potential human being that, like any other species, be it plant or animal, will, given a genetic and structural suffi ciency, proceed to grow in a species-typical way. What we see in maturation is as much an unfolding as it is a moulding. When we begin to see this unfolding from an evolved perspective and are able to liken and distinguish ourselves from our animal relatives then the full impact of what it is we need in order to grow and fl ourish, both as individuals and as a species, is more easily recognised.

Increasingly, we are beginning also to understand that the brain is constituted of a number of special-purpose units. These may be called small minds (Ornstein 1986), modules (Fodor 1985) or special intelligences (Gardner 1985). These individual, special functional units exert various effects on and through consciousness. They are most easily revealed by experimental research and also examination of the functioning of brain-damaged subjects. The human power of reason is now seen as a special faculty which can operate relatively untainted by personal needs (e.g. mathematical reasoning) or, alternatively can be recruited to fi ll in the gaps of an already crudely formulated reality thrown up by smaller functioning units for the interpretation of experience. Hence, the reasoning of the successful is different from the reasoning of the defeated; the reasoning of the loved is different from the reasoning of the abandoned; the reasoning of the neurotic is different from the reasoning of the psychotic, and the therapist needs to be schooled in these various ways reasoning is put to work. Additionally, the state of the physiological relations pertaining within the brain at any point in time profoundly affects our personal and social logics. This must be true otherwise no psychotropic medication would work, not to mention the power of drugs like LSD or alcohol.

Behaviourism is beginning to grapple with the problem of our innate capabilities for knowing and behaving (Rescorla 1988). The study of facial expressions (Tomkins 1981), innate sensory motor patterns (Leventhal 1984) and the study of the prepared basis for phobia (McNally 1987; Trower and Gilbert 1989) are also examples. It is no longer possible to regard humans as a tabula rasa without a developmental process (Kegan 1982; Goldstein 1985; Mahoney and Gabriel 1987). Watson’s behavioural triumph over MacDougall’s instinct theories, won in the 1920s, is coming to an end (Eysenck 1979; Goldstein 1985). We stand at one of those moments in history where it is possible to integrate what scattered details of knowledge of the human psyche we now possess. Sociobiology, ethology, biology, philosophy and of course, psychology are all enticing us with new ideas that demand an increasingly fl exible theoretical structure capable of dealing with both the evolved prepared basis of human mentality and its medium of modifi cation via the culture in which it comes to express itself. Hence, the complexities of human psychic life stretch out in wondrous diversity as perhaps at no other time in history.

This book is a personal journey through these complexities. It is an attempt to articulate the basic strands of human nature that can both resonate with the personal and yet be objective. In this I try to explain the basis of human suffering as arising from maladaptive deviations in the expression of our individual humanness. Such a grandiose scheme can never fully achieve its aim and this book must denounce any claims to be fully comprehensive. In casting such a wide net, it is sadly the case but inevitable, that there are parts of the net where the mesh is extremely fi ne and loosely woven. However, I hope this will not detract from the overall sketch that is given.

Outline